Groundhogs Day — The Start

Have you ever woken up and felt like you were reliving yesterday? That is the premise behind the movie Groundhog Day starring Bill Murray. Every day the main character wakes up just to relive the prior day all over again. While the movie script may be fiction, the idea behind Groundhog Day is something very real. Each day we strive to improve our lives so that tomorrow is better than today. But all too often we get that familiar feeling of "reliving yesterday" again and again. This feeling isn’t limited to a single day either. Next week/month/year frequently feels the same as last week/month/year. How can we combat this? How can we ensure that we are really making progress?

Benjamin Franklin observed this problem in himself and sought to make real change in his life by keeping a Virtue Journal. In this journal he listed out 13 virtues and tried to keep track of his progress in achieving them all. Over time, the same problems as before started to emerge. In the book Willpower Baumeister explains:

As he put it in Poor Richard’s Almanack: ’Tis easy to frame a good bold resolution; But hard is the Task that concerns execution. No matter how hard he tried, Franklin never could have kept that notebook clean, because some of the goals were bound to conflict at times. When, as a young journeyman printer, he tried to practice Order by drawing up a rigid daily work schedule, he kept getting interrupted by unexpected demands from his clients—and Industry required him to ignore the schedule and meet with them. If he practiced Frugality (“Waste nothing”) by always mending his own clothes and preparing all his own meals, there’d be less time available for Industry at his job—or for side projects like flying a kite in a thunderstorm or editing the Declaration of Independence. If he promised to spend an evening with his friends but then fell behind his schedule for work, he’d have to make a choice that would violate his virtue of Resolution…

Willpower: Rediscovering The Greatest Human Strength – Page 65

Whenever Franklin made progress in one area he would regress in another. He was still stuck in the same Groundhog Day trap! (He did make some net progress though). If Benjamin Franklin couldn’t avoid this trap despite his best efforts, how could anyone?

One might think that modern technology is the answer, but no clear solution has emerged. In fact, many contend that technology has only exacerbated the problem due to constantly interrupting our focus and hijacking our attention. While it is true that technology can be a tool to distract us, it can also be a tool to help us stay on track. Perhaps Franklin failed because his "technology" wasn’t good enough. Could digital journaling, pop psychology, project management theory, and a smartphone have been what Franklin was missing? I was desperate for a way out of the "Groundhog Day trap" and those were the only tools I had. It was worth a shot.

Living in the Distraction Age — Hooked by Nir Eyal

My first job out of college was working primarily in app development at Amazon (Goodreads specifically). I worked on a social reading app and spent much of my free time studying up on making the best apps. Despite being an engineer, I didn’t limit myself to just learning the technology. I also learned about the marketing, economy, and design behind the best apps. Working on a social reading app meant I read a lot, so it was only natural that I came upon the book Hooked by Nir Eyal.

Nir Eyal is an expert in psychology, technology, and design that has taught at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business and has consulted for major companies and publications. In Hooked he applies his expertise to apps and gives his blueprint for making an app that users can’t put down. His blueprint argues that there are 4 steps to getting users consistently engaged. They are:

- The Trigger – The Trigger is what makes a user engage with an app. There are two types of triggers: external and internal triggers. External triggers are something like an advertisement or a push notification from an app. Internal triggers come from within and usually correspond to a feeling or emotion. An example of an internal trigger is feeling bored and then opening a News app. Internal triggers are often much more powerful than external ones because they occur constantly throughout the day. Further, internal triggers form the basis for forming habitual behavior on the neurological level. It creates a link between an internal emotion and an app that can “satisfy” that emotion.

- The Action – The Action refers to how the app satisfies the trigger. For example, if the trigger was loneliness then your app might offer the action of sending a friend a message. The best actions are simple ones that maximize motivation and ability. That is, users should be sufficiently motivated to complete the action. Further, the app must enable the user to easily complete the action. Much of Twitter’s early success was due to enabling people to easily and quickly share online compared to other services at the time.

- Variable Reward – As a user engages with an app, it is important to reward them. An example of this is a “congratulations” message in diet-tracking app for meeting a calorie goal. One can make particularly engaging apps by offering a variable reward. Variables rewards were famously studied in Skinner’s Pigeon Experiment. He found that pigeons were more inclined to press buttons that dispensed variable amounts of food than constant amounts (even if that variable amount was sometimes less). Even pigeons like gambling! This same principle can be used to make users more likely to engage with an app again. Examples of variable rewards are coins in mobile games or likes on a Facebook post (you don’t know how many you’ll get). Our innate desire to seek out the largest reward will keep us coming back for more. These first three steps: trigger, action, and variable reward build the basis for forming a “habit loop” with an app.

- Investment – To ensure that users stick with an app it’s important that the user becomes invested. Consider online social networks such as Facebook. No one is willing to try out another app because they’ve already invested effort in adding friends on Facebook. This keeps users within Facebook’s “habit loop” rather than a competitor’s. Investment is the key to solidifying the “habit loop” created in the first 3 steps.

By applying these 4 steps one can create a truly engrossing app. This would serve as valuable knowledge to me not just as an app developer, but as a consumer.

I began to increasingly notice the "Hook Model" in apps that I used everyday. Instagram’s infinite-scroll discovery feed and Reddit’s karma system were perfect applications of the "Hook Model". I began to realize that I was spending the vast majority of my time engaged in "habit loops" engineered to keep me using an app. In a way, I felt taken advantage of. Was I using those apps because I enjoyed them or was I using them because I was hooked? I took this as an opportunity to delete the vast majority of the apps I had been using. At first it felt a bit strange, even a bit lonely. But as time passed I realized I was much happier. I found myself less distracted and more present in my activities. It was as if a dense fog clouding my mind had been lifted.

That doesn’t mean the "Hook Model" is bad though. The "Hook Model" is simply a tool. It can be used for good purposes and for bad ones – a point that Nir Eyal stresses in Hooked. I decided to try and use the "Hook Model" to help myself. At the time I wanted to get more into journaling. Journaling has been shown to have a variety of benefits with respect to personal growth and mental health. Plus I liked that idea of keeping a record of what I did. I sought out an app that used the "Hook Model" to keep me journaling – Day One.

The Beginning of History — Day One

Day One is a popular digital journaling app. It has a robust feature set that allows for custom typesetting, journal templates, photo entries, geo-tagging, voice notes, video, multi-device syncing, and labels/tags amongst other things. It also has a reminder system to keep you on top of your journaling. When I first started journaling with Day One I was not very successful. My journaling was excellent whenever I took the time to do it, but my problem was that I didn’t do it consistently. To correct this, I took advantage of the reminder and template feature to get myself "hooked" on the app. I set up daily reminders (an external trigger) and created a template for simple, routine daily entries (ease of action). Day One kept me motivated by awarding me with "hot streaks" when I consistently journaled well (variable reward). Finally, Day One started to notify me of historical journal entries. That is, Day One would give me notifications such as "1 year ago you wrote [text]" or "last time you were here you took this photo" (investment in the app). The strategy worked just as Hooked suggested and within a month I was a journaling religiously.

Journaling was a great exercise in writing and served as a good stress-relief technique. The greatest benefit from journaling, however, was being reminded of past entries and re-reading them. For the first time in my life I was able to easily go back and review my past thoughts and actions. I was able to compare today to yesterday or this month to last month. I was finally witness to my own history. This meant that I might finally have a tool to escape the "Groundhog Day trap". If I meticulously recorded my history, then I could actually know if I was "reliving yesterday". Perhaps if I kept this habit up and incorporated the power of technology, I really could escape the Groundhog Day trap.

A Framework for Growth — The Agile Methodology

Journaling wasn’t the only new system I was incorporating into my life at the time. I was also learning "The Agile System" at my work. Agile refers to a set of techniques used in project management and product development that promotes adaptive planning, continuous improvement, transparency, accuracy, and flexibility. It has historically been used as a framework for developing software, but has since been adapted for many other purposes. While the exact implementation of Agile can vary rather drastically from team to team, the principles are largely the same. Here I’ll explain the implementation of Agile that I know best.

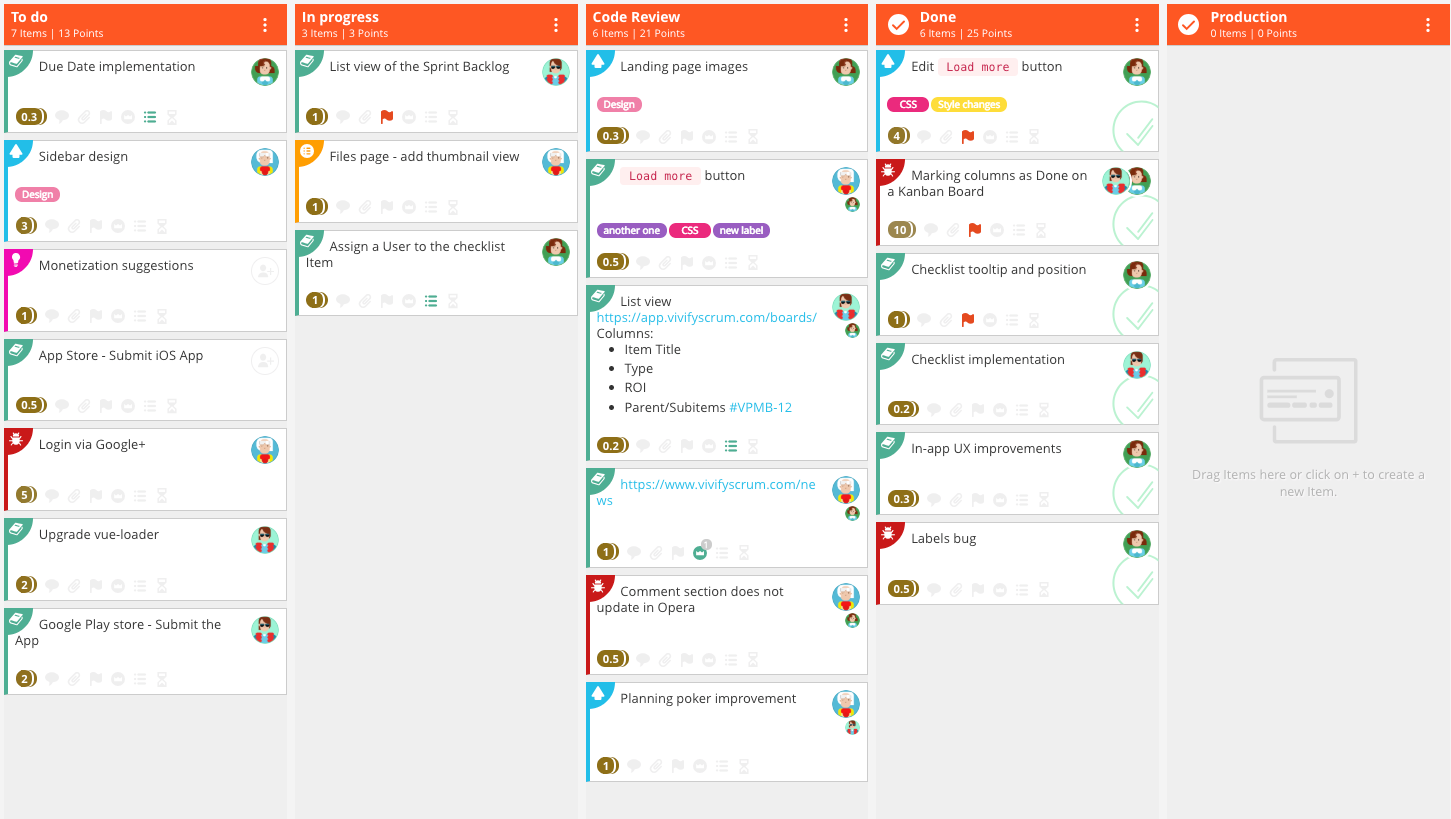

In most versions of Agile work is done in distinct blocks known as a "sprint". Sprints are generally 2-4 weeks in duration and once a duration is picked it is generally kept. Thus, work can be seen as a series of successive sprints. Each sprint follows the same structure. Below I give an example of a 2 week sprint. (Note that I’ve intentionally given a very simplified version of the Agile method here).

2 Week Sprint Outline

Day 1: Sprint Planning

Sprint planning begins by taking high level team goals and breaking them down into concrete tasks. For example, if a team goal is to build an app then one of the concrete tasks might be to build an "about us" page in the app. The next step is to determine the team capacity. A team of 4 engineers that code 5 hours per weekday each and have 3 total vacation days gives a capacity of 197 hours. The tasks from earlier are then assigned time estimates by the engineers. Estimates can be in the form of hours or broader categories that correspond to hours (a "large" task might equal 30 hours). The team now decides which of those tasks can fit in the sprint given its 197 hour capacity. Once a set of tasks is decided upon no other tasks should be added/modified during the sprint. That is, the plan should not be deviated from during the sprint to ensure consistency and progress. Teams often devote an engineer to handle unexpected issues that may occur during the course of the sprint. This engineer’s time is not considered when calculating sprint capacity so that unexpected items do not cause deviations in the outcome of the sprint. Finally, a series of "task cards" are created. These task cards are used to visually track the progress of the sprint and manage information such as to whom a task is assigned.

Days 2-13: Daily Standup

Standup meetings are held each day for the remainder of the sprint. The purpose of these meetings is to get a brief status report on each item in the sprint and check-in on the overall status of the sprint. The meeting is meant to be quick and effective. It should never take more than 10 minutes and any longer conversations should be taken offline. This is generally done by going through each of the "in-progress" tasks and hearing a brief progress update from whomever is working on the task. A common alternative to this is each team member giving a status update on what they’ve been working on. Finally, the team leader give an overall status report on the sprint to ensure proper coordination amongst outstanding tasks. When done properly these standup meetings help foster better communication and transparency. Further, they help keep the team on track and help the team identify roadblocks early. Lastly, it is important to record the time spent working on each task. This will be important during sprint retrospective later.

Day 14: Sprint Demo

Sprint demo is when all of the work accomplished during the sprint is shown to the team. Engineers can exhibit the new functionality they’ve built, designers can show the latest sketches/mocks they’ve been working on, project managers can show the latest product insights they’ve gained, and so on. The purpose of sprint demo is to give everyone a chance to take pride in their work and show off what they did during the sprint. Also, sharing in a group fosters more collaboration, creates accountability, and serves as a good indicator of the team’s overall progress and direction.

Day 14: Sprint Retrospective

Sprint retrospective gives the team a chance to review, reflect, and iterate on their last sprint. It begins by having team members share "what went well" and "what could be improved" for the sprint that was just completed. Examples include "we caught bugs before shipping to customers" and "we forgot to provide translations for the latest blog post". Things that can be improved upon, such as forgetting to provide translations, are given an action item such as "add translation task to all future sprints". Actions items are then assigned a point person and are reviewed during the next sprint retrospective to make sure they’ve been properly implemented. Finally, the team checks if their time spent on all tasks/tickets actually matches their initial estimate for the sprint’s capacity. The sprints capacity is then adjusted to account for this. For example, if the team only did 4 hours of coding work every day instead of the estimated 5 hours then the next sprint should use 4 hours per day as the basis for estimating coding work. Conducting a sprint retrospective is critical for ensuring that next sprint goes better than the last one. Improvement only happens by addressing and iterating on the missteps from the prior sprint.

Many teams have had great success using the Agile model detailed above. As a result, it is almost ubiquitous amongst software development teams and increasingly common with other types of teams. I came to the same conclusion after implementing and running the Agile model on my team at work. Our team was more efficient, less stressed, and finally making verifiable progress. All of this left me wondering, where else can the Agile model be applied?

How To Hack Yourself — Agile and You

At this point I had been journaling for several months and saw great progress. The techniques I applied from Hooked kept me committed, but I wanted to get more out of journaling. Specifically, I wanted my journaling to help me make progress as a person just as Ben Franklin’s Virtue Journal did for him. Luckily, I already had the answer right in front of me — The Agile Model. What if I implemented the Agile system for myself instead of just my team at work? I could use one week sprints to not just keep track of my life, but also improve my life. The benefits of trying this were immediately clear, namely:

- I’d have a concrete plan for what I wanted to achieve each week

- I’d end up with a detailed account of everything I had done each day and each sprint

- I’d continually improve my process during each week’s retrospective and thus increase my rate of progress each sprint

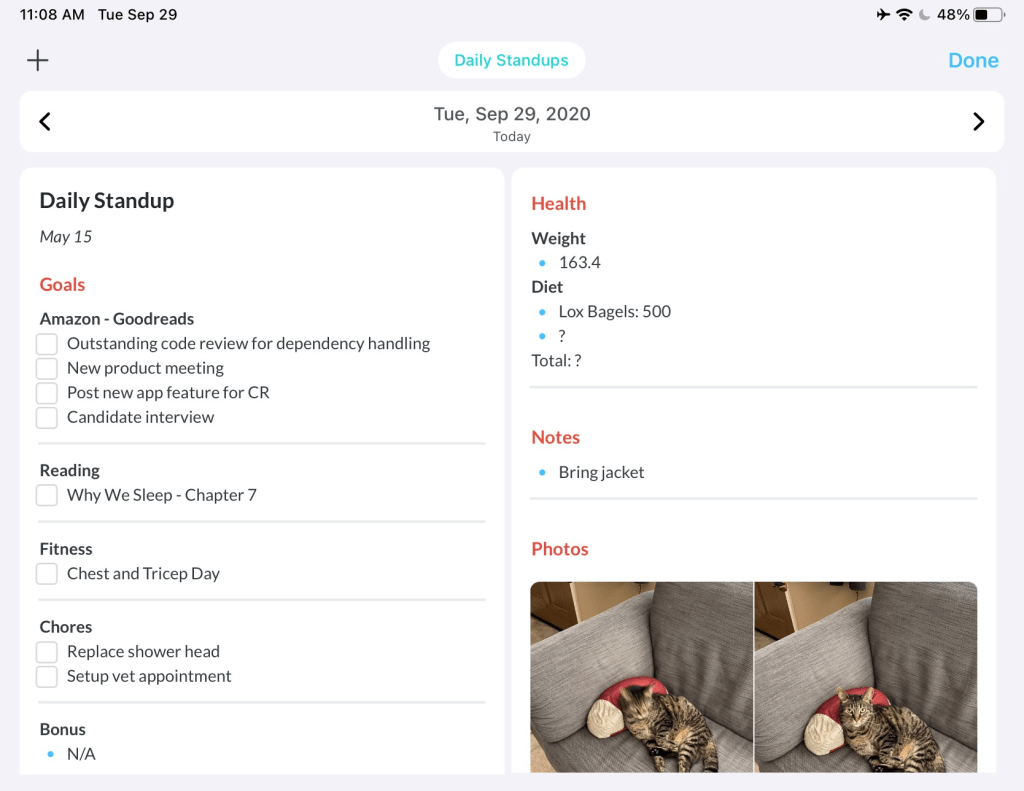

Day One was the perfect app for implementing my personal Agile model. Their template feature allowed me to create templates for sprint planning, daily standup, sprint demo, and sprint retrospective. Every Sunday I would conduct a sprint planning session for the week and lay out my high level goals as a function of my capacity. Each weekday I would have a daily standup and review the smaller tasks that I needed to complete. Finally, on Saturday I would conduct a sprint demo and retrospective. I’d go over what I had achieved during the sprint and then make improvements to my process to make the next sprint go even better. Below are some examples of my initial system:

Over the next year I used and improved my "Personal Agile Model". It was a huge success almost immediately and one of the most impactful life changes I had ever made. It seemed like I had finally found a true solution to the Groundhog Day trap. By keeping a record of my life I was able to actually compare today to yesterday. Further, by constantly working to improve my life I could ensure that today was better, and therefore different, than yesterday.

The Limiting Factor — Mental Health

For a while it seemed like I had escaped the Groundhog Day trap. Each day was (generally) better than the prior. I was able to see and feel my life improving in real time. Unfortunately, after the first year my progress began to plateau and I hit a wall. Whenever I made progress in one area, I began to falter in another. I had ran into the same issue as Benjamin Franklin did with his Virtue Journal. Luckily, all of the data I needed to solve this problem was literally right in front me — my journal.

I reviewed all of my sprints and journal entries and a few key suspects emerged. They were:

- Distractions by technology (Reddit, instant messaging, etc)

- Lack of focus and stress due to intrusive thoughts (worry or anxiety, such as “Oh, will we still meet that project milestone?”)

- Tiredness from doing too much work and feeling “burnt out”

The common thread between all of these was "the mind". I wasn’t running up against physical limitations such as my health. (I had already hacked my physical health in previous projects here and here). It seemed my limiting factor was mental health. In order to investigate further I read The Disordered Mind by Eric Kandel.

Mental health has historically been an elusive and less concrete concept than physical health. This makes sense intuitively. If someone is having trouble walking and has a large bruise/bump on their leg, then it’s obvious what’s causing the problem. If someone is depressed, however, it’s not so easy to look inside their brain and point to a clear reason why. It’s often easier to believe the cause is a "poor attitude" or "lack of motivation". The truth is that the biological underpinnings of mental health are far more complicated than physical health and we still don’t completely understand them. However, for the first time in history we are finally getting close. In fact, with each advancement we are realizing that mental health is no different than physical health. Consider the following example explaining the biology and chemistry behind the symptoms associated with recurring stress:

Excessive concentrations of cortisol destroy synaptic connections between neurons in the hippocampus, the region of the brain that is important in memory storage, and neurons in the prefrontal cortex, which regulates a person’s will to live and influences a person’s decision making and memory storage. The breakdown of synaptic connections in these regions leads to the flattening of emotion and to the impaired memory and concentration that accompany major depression and chronic stress.

The Disordered Mind: What Unusual Brains Tell Us About Ourselves – Loc 960

Now that we have begun to understand the science behind our minds, we can finally start to use technology to aid the mind. Science fiction predicts some bizarre futures. Psychopass predicts a dystopian future where the government will use mental wellness exams to keep us in check. The Dark Forest predicts we will develop technology to help motivate us and mold our feelings. Actual science shows we may not be too far off from a machine to treat depression:

Mayberg was familiar with these advances and thought that slowing the firing rate of neurons in area 25 might relieve the symptoms of depression. She used deep-brain stimulation in the anterior insula region to treat twenty-five people whose depression was resistant to treatment. She collaborated with a team of neurosurgeons, first at the University of Toronto and then at Emory, who implanted the electrodes. When she turned on the electricity in the operating room, she saw almost immediate changes in the patients’ mood. The patients no longer felt the unending psychic pain characteristic of depression. Moreover, the other symptoms of depression gradually lifted as well. People recovered and were stabilized for the long term.

The Disordered Mind: What Unusual Brains Tell Us About Ourselves – Loc 1192

While we aren’t quite at the point of rewiring our own brains yet, we do know enough to start applying some basic mental hygiene to keep our minds healthy.

How To Not Burn Out — Headspace and Mental Runbooks

On Friday June 8 of 2018 I was traveling to Chicago to explore the city and attend my brother’s graduation. As my flight was about to take off, I got a text that Anthony Bourdain had died by suicide. Stunned, I googled the news just to be informed that the Wi-Fi on the TV-less flight wasn’t working. I sat there, bored and disconnected, wondering about the news. How could that happen to someone that had turned their life around and inspired countless others (such as myself) to travel? While I could never answer that specific question, I could think of how to prevent similar things from happening in the future. How could I use technology and my research on mental health to prevent something like this?

I began to sketch out an app on the flight called "Mental Runbooks". A Runbook is typically an engineering manual on what to do when something goes wrong in a system. For example, there might be a section on "what to do if power is lost" or "how to manually reboot the system". The idea is that during a stressful scenario people will not act rationally. Therefore, one should be prepared by writing out what to do ahead of time so that in the case of an emergency all one has to do is follow a simple series of steps. I wanted to apply this same concept for common mental health situations such as experiencing anxiety, intense procrastination, negative thoughts, etc. My theory was that perhaps if Bourdain had such a tool he’d still be here today.

Over the next few months I read up on and learned a variety of techniques for keeping one’s mental health in check. Most of the techniques were small tricks such as physically removing distractions like smartphones, creating boundaries between work/home, noting and acknowledging intrusive thoughts in order to resolve them, etc. Some of them were broader concepts though, such as presence — being fully engaged in the current moment.

One particularly useful tool I discovered during my research was Headspace. Headspace is an app that uses guided meditation to help users be more present. The theory is that meditation serves as practice for being present. When one meditates they must clear their mind and focus solely on their breathing. This is in essence being present. Thus, by practicing meditation one can "train" their ability to be present. Headspace encourages applying the same principle when engaging in other activities. For example, when typing an email one’s attention should be on just that. When the mind strays to an intrusive thought or a notification from an app, one must simply recollect themselves and return their focus to the task at hand.

Presence is an extremely powerful concept because it can shield against distractions and anxiety. By routinely clearing the mind and striving to maintain focus, one becomes aware of pestering distractions like social media. Further, one can get a leg up on anxiety by being aware of intrusive thoughts and avoiding getting sucked into them.

By this point I had learned a ton about mental health, but hadn’t made much progress on my Mental Runbooks app. I simply didn’t have the time to build it. Nonetheless, I did want to incorporate the lessons I learned about mental health into my "Personal Agile System" and overcome my progress plateau. The problem was that I wasn’t sure how to do it. Incorporating headspace and some other tips and tricks was helpful – but not enough to take my "system" to the next level. I had all of the right ideas behind what I wanted, but I couldn’t put a name to it.

Coming Full Circle — Indistractable

In October 2019 Nir Eyal, the author of Hooked, came out with a book titled Indistractable. Prior to the book’s release, he spoke to my organization at work. He told us a brief story that inspired him to write the book. He also recounts it at the start of the book:

“Daddy,” she said, “what would your superpower be?”

“Huh?” I grunted. “Just a second. I just need to respond to this one thing.” I dismissed her as I attended to something on my phone. My eyes were still glued to my screen, fingers tapping away at something that seemed important at the time but could definitely have waited. She went quiet. By the time I looked up, she was gone.

I had just blown a magical moment with my daughter because something on my phone had grabbed my attention. On its own, it was no big deal. But if I told you this was an isolated incident, I’d be lying. This same scene had played out countless times before.

Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life – Page 5

In an ironic turn of events, Nir Eyal had become victim to the exact same techniques he had popularized in Hooked. Nir Eyal’s experience had in a way mirrored my own. Over time I had come to realize the dangers of modern app design and the importance of mental health. And much like Nir Eyal, I had come up with a personal system to deal with said issues. Nir Eyal, however, had come up with a name for the system I was trying to put together. I was trying to be indistractable. That was what I needed to be if I wanted my system to work and to escape the Groundhog Day trap.

In Indistractable Nir Eyal lays out his take on what one needs to do to become indistractable. The first step is defining a set guiding goals/areas-of-focus. This should include everything in one’s life — career goals, family, and personal activities. A simple example might be: career, wife, puppy, swimming, and video games. It’s critical that one identifies what is important to them before deciding how to spend their time/focus. Once that is done, it becomes possible to define traction and distraction. Traction refers to actions that move us towards what we really want (our goals, responsibilities, etc.). Distraction refers to activities that don’t. We tend towards traction or distraction based on external and internal triggers. Nir Eyal’s "Indistractable Model" provides a framework for optimizing for traction. The model has four key tenets:

- Master Internal Triggers: The first step to mastering internal triggers is to identify what they are. This can be done by looking for the discomfort that precedes the distraction. For example, if one opens a gaming app when stressed, then the internal trigger is likely that type of stress. Once an internal trigger has been identified it is important to keep an eye out for them. Often the difference between succumbing to such a trigger or not is knowing how to identify a triggering moment. One common technique to avoid internal triggers is “surfing the urge” whereby one promises to try and make it “5 more minutes” before succumbing to a trigger. More frequently than not one lasts the 5 minutes and can then do 5 more. Another technique is reframing the task. Instead of simply trying to accomplish the task, try and find a more efficient way to do it. Play games and use tricks from Hooked to make the task fun and avoid common internal triggers. Lastly, acknowledge that succumbing to some internal triggers is inevitable. The goal isn’t completely avoiding distraction; it is minimizing distraction.

- Make Time for Traction: In order for an activity to count as “traction” it must tie back to a guiding goal/area-of-focus. Thus to maximize traction, one should make sure most of their time can be tied back to those guiding goals/areas-of-focus. The best way to do this is by creating a timeboxed schedule. This means dividing each chunk of the day into 15 minute to 1 hour blocks of focused activities. Keep in mind that activities like friends, relaxing, and chores should be areas-of-focus and therefore be timeboxed activities. Even activities like playing games or watching tv are included — just make sure to not give them more time than necessary. Timeboxing our schedule forces us to be wise and intentional about how we spend our time. Additional techniques such as maintaining clear boundaries between “work time” and “family time” can make this practice easier. Don’t forget to plan timeboxes with family, friends, and coworkers so that expectations are balanced and transparent.

- Hack Back External Triggers: External triggers such as smart devices, app notifications, and television screens often impact our ability to stay on focused during a timebox. When executing a timebox it is best to remove any potential external triggers that do not serve the timebox’s objective. External triggers can be identified in real time by asking oneself, “Is this trigger serving me or am I serving it?” Often external triggers are in the form of other people that interrupt. This can be mitigated by explicitly scheduling time for focused work and time for meeting with others. Having “office hours” is a clear sign to colleagues that there are proper and improper times to interrupt. Additional techniques include explicitly marking oneself as focused by wearing headphones and turning on “do not disturb”. The book offers a variety of specific techniques for common traps such as email, group chats, meetings, and smartphones.

- Prevents Distraction with Pacts: In the Odyssey Odysseus avoids the irresistible temptation of the Sirens by having his crew tie him to his ship’s mast. He tells his crew to not release him despite all of his pleas until they had passed the Sirens. This type of action is known as an “precommitment” pact. The fundamental principle is to configure a future situation so that one can’t avoid doing the right thing. That is, make a plan that can’t fail. There are three common forms of precommitment pacts that aid with preventing distraction. Effort pacts work by making an unwanted behavior more difficult to engage in. A famous example of this is the kSafe. The kSafe is a locking container that can’t be opened (other than by breaking it) for a set period of time. Price pacts involve putting money on the line to encourage one to do the right thing. An example of this is betting a friend that you’ll get a task done. Price pacts are a good tool, but are most effective when used infrequently. Lastly, identity pacts work by having one adopt an identity that inspires themselves to be better. For example, labeling oneself as a “vegetarian” provides encouragement to avoid meat. Studies have shown that a person is far more likely to engage in an action when it is an expression of self rather than a rote behavior.

Many of these strategies were very similar to the ones I had discovered. Armed with the "Indistractable Model" and my own experiences I sought to create a holistic app for productivity, focus, mental health, planning, etc. I wanted to create the ultimate tool for escaping the Groundhog Day trap permanently.

Building Fast and Lean — SwiftUI

I wanted to break my progress plateau and escape the Groundhog Day trap quickly. This meant I needed a simple but powerful tool to build my "ultimate app". Luckily, SwiftUI had just been released by Apple and was finally being picked up by developers. SwiftUI is a robust framework for building declarative user interfaces. Its elegant design allows for clear and concise code to be written quickly. Further, it automatically works on all Apple platforms and integrates with existing Apple technologies. SwiftUI differs from traditional UI programming by combining the code for the "view" and the "controllers" that power the view. Instead of managing all of the interactions between the view, controllers, and underlying data, the programmer simply declares how the view and controllers should operate as a function of the data. The underlying data serves as a "single source of truth" from which the rest of the state of the app is derived. The code is so clear that you arguably don’t even need any experience to understand it:

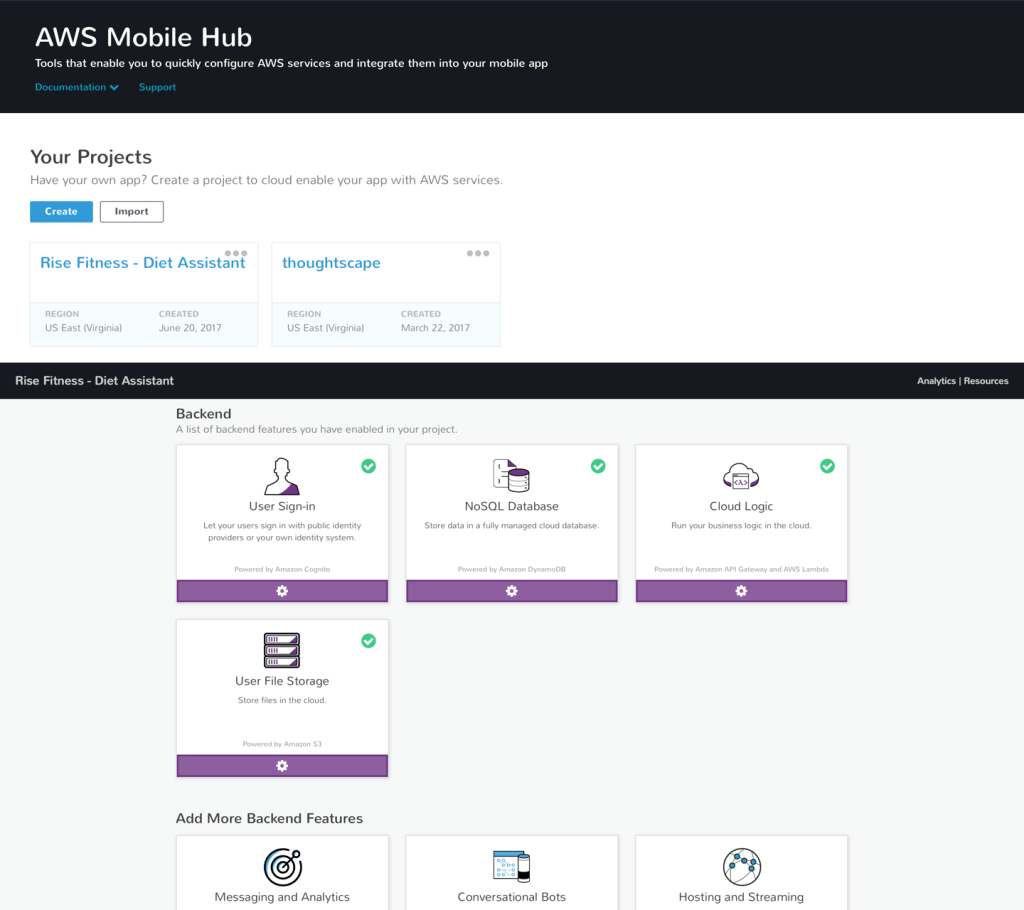

SwiftUI allowed me to quickly build out all of the visuals, logic, and functionality behind my app. My only remaining choice was how I wanted to store and represent the underlying data.

I chose to use Core Data to persist my app’s data. Core Data is a built-in Apple tool for storing data. It provides a ton of functionality such as large-scale storing of a variety of types of data (even photos), background data tasks, undo/redo operations, and integrations with other Apple tools such as iCloud syncing. It also interfaces well with SwiftUI through simple "fetch requests". Lastly, all of the data is stored locally and doesn’t require any internet to use. Thus it is both secure and private.

I was able to use SwiftUI and Core Data to quickly and elegantly build my app without cutting any corners.

Making A Plan — The Weekly

I began building my app by combining the sprint planning step of my Personal Agile Model with the goals and areas-of-focus that form the basis for the Indistractable Model. As such, the first step in the app is the weekly planning phase whereby a user establishes their areas-of-focus for the week and corresponding high-level goals. This process is demonstrated below in the segment of the app known as "The Weekly":

Once weekly goals and areas-of-focus have been setup, the user begins their weekly "sprint" and starts using the other modules within the app (such as daily standup and timeboxes). Throughout the course of the sprint the user can come back to The Weekly and mark goals as completed. Once the sprint is complete, the user returns to The Weekly to do their sprint retrospective. This allows the user to reflect on what went well, what went poorly, and what to improve for their next sprint. This cycle of reflection, iteration, and improvement is key to ensuring growth week over week. This can be seen below:

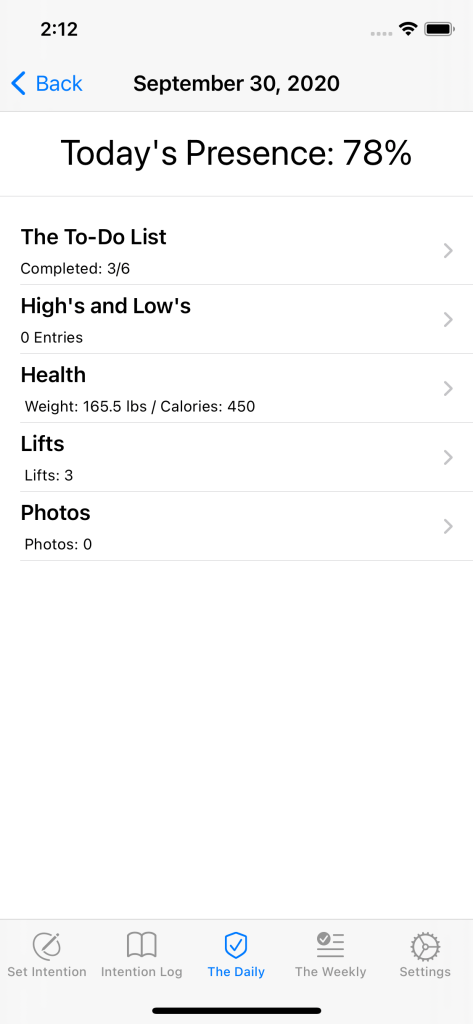

Staying on Track — The Daily

Once the weekly sprint has been setup, each day of the week is managed through "The Daily" segment of the app. Within The Daily users setup and manage their daily to-do list. All to-do’s must tie back to the original goals/areas-of-focus setup in The Weekly. This forces the user to the be cognizant of engaging in any tasks that deviate from their intended weekly plan. This list of to-do’s also serves as the basis for the daily standup whereby the user reviews their work plan for the day. This is demonstrated below:

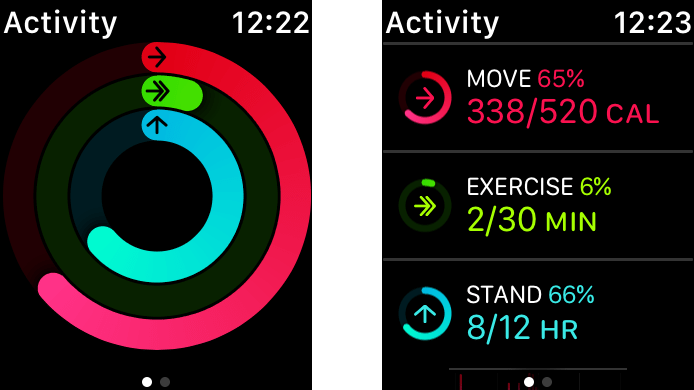

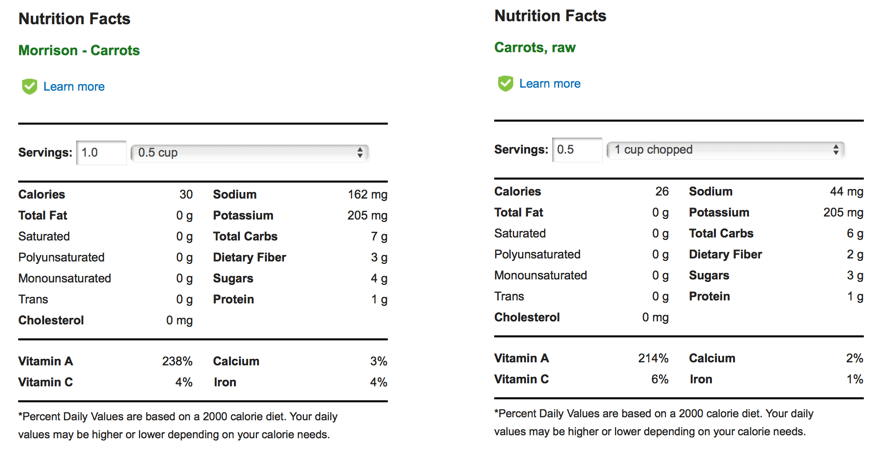

The Daily also offers others modules in addition to the to-do list. These custom modules provide detailed tracking/reporting for special activities. Currently the app supports additional tracking/reporting for health, sleep, workouts, daily review, and photos. These additional modules help users keep other important daily activities in check. The goal is to ensure a solid foundation for productivity by optimizing for physical health, self-reflection, sleep, mental health, etc. Often the reason for plateauing or hitting a wall is lacking that strong foundation. Some of these modules are demoed below:

Being Present — The Intention Log

The primary feature of the app is "The Intention Log". The Intention Log is a process for conducting focused work and being present. The process works as follows:

- Set An Intention: The user begins by defining an “intention”. An intention is a clear and concise activity that the user plans on engaging in. Examples include: getting showered/dressed, emailing direct reports, edit TPS reports, bathe cat, etc. By explicitly setting an intention, the user can know whether or not they are staying focused. More often than not we fall into distraction traps because we never explicitly decided on what we wanted to do in the first place. Once an intention and duration is decided upon, the user proceeds to the next step.

- Execute The Intention: The user is then presented with a screen that reiterates the planned intention and shows a countdown timer based on the set duration. The user is reminded to remove external distractions and of other useful tips/tricks from Indistractable. The phone is automatically set to “do not disturb” and a notification is only sent once the duration has finished. The purpose of this step is to create a “bubble of presence” whereby the user will not be distracted by external triggers or get trapped in intrusive thoughts. Within this bubble of focus users can engage fully in their planned intention. It is meant to be no different than meditation — one’s mind should be completely focused on the intention to make time for traction.

- Tag The Intention: The user then adds tags to the intention from a list of common labels. This is useful for future analytics and record keeping. It also forces the user to consider how their intention ties back to their goals/areas-of-focus and whether they are engaging in traction or distraction.

- Rate The Intention: After tagging the intention the user indicates how they felt during the intention: ecstatic, happy, meh, sad, or angry. The user must wait 5 seconds before making a choice. This forces the user to really reflect on the intention and how it made them feel. Understanding and being in-tune with one’s emotional state helps the user manage their mental health and select future intentions in a productive way. Further, this feeling data can be used along with tag data to draw important conclusions. For example a user can use this data to learn what activities bring them joy and what activities cause frustration. This information can then be used to plan intentions in a way that leads to better outcomes.

- Review The Intention: Finally, the user conducts a more formal review of the intention. They are prompted to answer “what went well?”, “what could be improved?”, and “what was interesting?”. This process is very similar to the sprint retrospective process, but applied to each intention. By reflecting and making corresponding adjustments, we setup ourselves up for more success in the future. Constantly reviewing and reflecting on our actions forces us to be more in-tune with our lives and more present. It stops us from sleepwalking through life due to distracting technology or other mental health issues.

Lastly, users are given notifications throughout the day if they have failed to complete/review an intention or have yet to start an intention after a while. A full demo of this is shown below:

Users can easily go back and review/edit past intentions as demonstrated below:

Lastly, users can track the percentage of their day spent "present" within The Daily:

I never managed to come up with a good name or logo for the app and ended up just calling it "The System". Despite not having a finished app name, I was finally done with it and ready to start using it. It was time to escape the Groundhog Day trap forever.

The Ultimate Stress Test — Coronavirus and The System

I was using my new app and doing excellently. I had blown past my old plateaus and was making good progress. Everything was going great… and then Coronavirus struck. It was the ultimate irony. I had spent years building a system to escape the Groundhog Day trap just to be thrown into a global catastrophe that basically required the world to live like a groundhog during winter in order to survive. Good luck making today different than yesterday when most things are shutdown, social contact is severely limited, and all work is done remotely (not to mention being literally trapped indoors during the ensuing California Wildfires).

Despite all of this, I’ve managed to not just survive but thrive. "The System" was exactly the tool I needed for all of this. It kept me on track, maintained my mental health, ensured I made progress, and helped me escape the many pitfalls associated with life during Coronavirus. By making weekly/daily plans and being completely present during my intentions I was able to largely escape the mental anguish that has affected so many during this pandemic. The System really did live up to my original vision. I was able to intelligently use technology, psychology, design, and science to escape the Groundhog Day trap — even during one of the most difficult times in modern history. I got past Benjamin Franklin’s problem of making progress in some areas just to falter in others by continually honing The System. It was finally time to stop reliving yesterday and embark upon today.

Where We Are and Where We’re Going

I’ve continued to make improvements to The System since completing it. I have, however, taken a break from putting all of my spare time into it. I want to let The System run for a while and see how it does before making any more significant changes. Nonetheless there are many things that I would like to do. I would like to make a final version of this product and put it on the App Store for everyone to be able to use and benefit from. This should be relatively easy because it has no 3rd party or online dependencies. Other ideas include:

- Reporting of common metrics during sprint retrospective

- Suggestions based on past activity using AI/ML

- Building additional features to boost engagement and presence

I’ve included a final holistic demo below: